Adding and Updating Columns in the Florida Salaries Data

Table of contents

- Beware of updating the database

- Adding columns to an existing table

- Updating columns

- How to screw things up

Editing the actual data in a database is far less convenient than it is with spreadsheets. The good part of this inherent clunkiness is that it's hard to inadvertently alter the data, in the way that a clumsy mouse-click can accidentally and silently change a cell or a row.

The tradeoff is that we have to be much more deliberate when making changes to the database. But we're already used to the idea of having to write and execute code just to view the data, so it shouldn't be a surprise that we need to do the same when altering the data.

Beware of updating the database

Before we move on and get into the elaborate explanation, I'll just state what we want to do to our existing data tables. The florida_positions has a column named AnnualSalary that contains a lot of blanks. This screws up our ability to sort that column.

So, for all rows in which AnnualSalary is _blank, we want to set it equal to something like 0 or NULL.

This kind of SQL statement is referred to as an UPDATE. To update a column's values, the SQL syntax looks like this (but don't run this yet yourself):

UPDATE florida_positions

SET AnnualSalary = 0

WHERE AnnualSalary = '';

Seems simple enough, right? The syntax is pretty tame. However, if you make a single typo, such as this kind of typo, which I make all the time especially when copy-pasting from other code:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET AnnualSalary = 0;

WHERE AnnualSalary = '';

There's an early semi-colon there, which causes the UPDATE statement to run without the WHERE condition. This means that every row is affected by this UPDATE action, i.e. AnnualSalary is now set to 0. And there is no way to reverse this unless you've written a bunch of other code to prepare for this. Which you probably haven't.

Duplicate, don't overwrite

Generally, the best strategy is to duplicate an existing column, and then apply changes to the duplicate column:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET AnnualSalaryCopy = 0

WHERE AnnualSalaryCopy = '';

That way if a query goes badly, we can always refer to the original column.

So this is why we're going to learn how to add columns to an existing table before doing a relatively simple UPDATE statement.

How to backup a SQLite database

I haven't explicitly mentioned this, but if you've been using SQLite and a SQLite client all this time, then you've probably noticed that opening a SQLite database is basically like opening a file. That's because a SQLite database is a file, just like spreadsheets are usually .xls files on your hard drive. This means you can make copies of any given SQLite database.

So if it bothers you that you could potentially screw up a database in such a way that you have to recreate it…just make a backup file before you do any work.

Adding columns to an existing table

Adding columns to a table involves a new SQL statement: ALTER TABLE. The ALTER TABLE-variety of statements can do only two things:

- Rename a table

- Add a column to an existing table

Notice that there is no ability to rename or drop a column. That's just the way SQLite keeps things simple…so…try to be careful when altering a table (or when creating one in the first place). Of course, we always have the option of dropping and recreating tables, then reimporting the data…but we obviously don't want to do that for fun.

The syntax for adding a column to a table looks like this:

ALTER TABLE "name_of_existing_table"

ADD COLUMN

"new_column_name" NEW_COLUMN_DATATYPE;

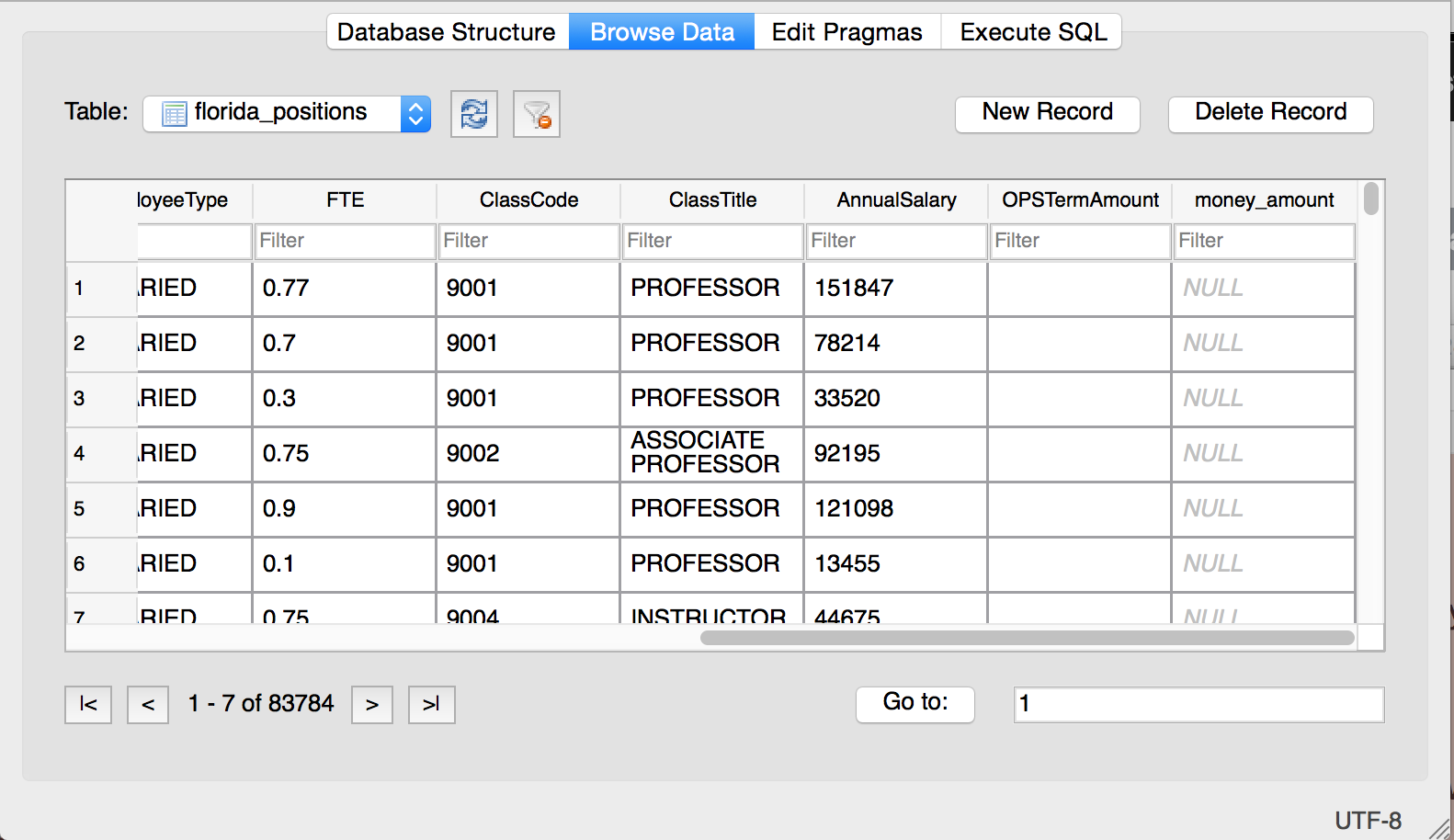

Creating an new, empty money_amount column

To add a new INTEGER-type column – with the name of money_amount – to our florida_positions table:

ALTER TABLE "florida_positions"

ADD COLUMN

"money_amount" INTEGER;

If you browse the data in florida_positions, you'll see the new money_amount column full of NULL values:

And that's all there's to adding new columns to a table!

Don't sweat the small table mistakes

But again, if you screw up a column's name or type – you can't remove it from a table and you'll have to just make an entirely new table (other flavors of SQL aren't as strict on this). But for the most part, creating useless columns won't really harm your database. Unless you're OCD and hate the idea of useless clutter that has otherwise no effect on your analysis.

If you do need to fix a table-level mistake, you have to make a empty, pristine copy of the messed-up table (sans the mistakes of course) and pour data from the bad table into the new copy. This is actually easily doable through more SQLite code…but I'll let you figure that out on your own if the occasion arises.

Updating columns

This next section contains syntax for a new type of SQL statement: UPDATE

Darned blank values!

Just to reiterate the problem from the previous tutorial, we ran into a problem when trying to sort florida_positions by the AnnualSalary column. Many rows had blank values for the AnnualSalary column – typically, positions that were temporary and had money in the OPSTermAmount.

So when trying to sort AnnualSalary in reverse order, blank values apparently come out on top, making it difficult to see the actual highest salaries:

SELECT LastName, ClassTitle, AnnualSalary, OPSTermAmount

FROM florida_positions

ORDER BY AnnualSalary DESC

LIMIT 5;

| LastName | ClassTitle | AnnualSalary | OPSTermAmount |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADAMS | ASSISTANT PROFESSOR | 2550 | |

| ADAMS | PROFESSOR | 6000 | |

| ADAMS | INSTRUCTOR | 2400 | |

| ADETU | INSTRUCTOR | 4001 | |

| AKINS | INSTRUCTOR | 600 |

Of course, we could get around this problem by adding a WHERE filter – e.g. WHERE AnnualSalary != '' – but it would be more convenient if such irrelevant rows were implicitly ignored – or at least put at the bottom – when doing sorts by AnnualSalary.

Let's do a quick COUNT query to see what AnnualSalary contains: obviously there are blank values. But are there NULL values? How about 0 values? The following query excludes all rows in which AnnualSalary is not between 1 and some arbitrarily high number:

SELECT AnnualSalary, COUNT(*)

FROM florida_positions

WHERE AnnualSalary NOT BETWEEN 1 AND 1000000000

GROUP BY AnnualSalary;

Looks like the only non-zero, non-numerical number is a blank cell:

| AnnualSalary | COUNT(*) |

|---|---|

| 23919 |

Using UPDATE to copying one column into another

First of all, if you haven't created the money_amount column in the florida_positions table, as described earlier in this lesson, please do so before continuing.

OK, having created that money_amount column, you should have noticed that it is entirely empty. Let's copy over all the values from AnnualSalary to money_amount. This requires the simplest form of the UPDATE statement:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary;

The meaning of SET

The syntax is simple enough, but pay special attention to the SET keyword. In the context of the SET keyword, the equals sign now performs an assignment: i.e. it sets the value of the thing on the left of the equals sign to whatever is on the right side. In the snippet above, the money_amount column for every row in the florida_positions table is set to the corresponding value of AnnualSalary.

If you ran the above UPDATE statement, the changes will have taken effect more or less immediately. Let's check out the result using a simple SELECT statement:

SELECT LastName, ClassTitle, AnnualSalary, money_amount

FROM florida_positions

LIMIT 5;

The result:

| LastName | ClassTitle | AnnualSalary | money_amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABATE | PROFESSOR | 151847 | 151847 |

| ABAZINGE | PROFESSOR | 78214 | 78214 |

| ABAZINGE | PROFESSOR | 33520 | 33520 |

| ABDELRAZIG | ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR | 92195 | 92195 |

| ABLORDEPPEY | PROFESSOR | 121098 | 121098 |

That's all there's to updating a column.

And that's it. But word of warning – it is entirely easy to screw this up. For example, by mixing up the left side with the right side, like so:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET AnnualSalary = money_amount;

/* JUST IN CASE IT'S NOT OBVIOUS: DON'T RUN THIS!!!*/

Congratulations, you've just set the AnnualSalary column to whatever was in the money_amount column. Seeing how money_amount column is a column we just made up, you've just irrevocably changed the original data. Time to start over from the import process.

(Or start from a backup of the database, if you've made one).

Updating cells on a condition

Now that money_amount is the exact duplicate of AnnualSalary, that means it contains the exact same blank values. We can confirm this with a quick SELECT and GROUP BY:

SELECT AnnualSalary, money_amount, COUNT(*)

FROM florida_positions

WHERE

AnnualSalary NOT BETWEEN 1 AND 1000000000

GROUP BY

AnnualSalary, money_amount;

| AnnualSalary | money_amount | COUNT(*) |

|---|---|---|

| 23919 |

So, let's write an UPDATE statement that does the following: for every row in which money_amount is blank, set money_amount to NULL.

Notice how I make no mention of the AnnualSalary column. There's no need to refer to it any longer if money_amount is its exact duplicate.

Here's the UPDATE statement to run:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = NULL

WHERE money_amount = '';

Did it work? SQLite doesn't really give you much feedback (other SQL databases will tell you how many rows were affected). Let's re-run the previous SELECT statement to see if anything changed:

SELECT AnnualSalary, money_amount, COUNT(*)

FROM florida_positions

WHERE

AnnualSalary NOT BETWEEN 1 AND 1000000000

GROUP BY

AnnualSalary, money_amount;

The subtle change is that money_amount is NULL, which is a special value that is not the same as a blank (or empty text string) value.

| AnnualSalary | money_amount | COUNT(*) |

|---|---|---|

| NULL | 23919 |

Besides that subtle difference of nomenclature – which, honestly, has limited obvious real-world impact to us right now – one difference between NULL and an empty string is that NULL is ignored when sorting.

So let's re-run our the sorting-by-top-salary query from earlier in this lesson – except, we'll sort by money_amount instead of AnnualSalary:

SELECT LastName, ClassTitle, money_amount, OPSTermAmount

FROM florida_positions

ORDER BY money_amount DESC

LIMIT 5;

Bingo!

| LastName | ClassTitle | money_amount | OPSTermAmount |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRIEDMAN | PROFESSOR | 961281 | |

| GUZICK | PROFESSOR | 905000 | |

| KESHAVARZI | ASSISTANT PROFESSOR | 730685 | |

| CHALAM | PROFESSOR | 680685 | |

| FUCHS | PROFESSOR | 661340 |

Using the money_amount column to aggregate salaried and temp workers

In the previous tutorial, I briefly mentioned the meaning of OPSTermAmount. The values in this column, according to the state of Florida's human resources webpage, refer to payments for temporary/short-term positions.

In other words, every record referring to a salaried position – i.e. having a non-blank value for AnnualSalary – should not have a value in OPSTermAmount.

And vice versa, everyone who has a non-blank amount in OPSTermAmount should have a blank value in AnnualSalary. Let's confirm this with a SELECT and COUNT query.

The following query – which filters for all rows in which both OPSTermAmount and AnnualSalary have non-zero numerical values – should return 0, as in, there are zero rows which meet that condition:

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM florida_positions

WHERE

OPSTermAmount BETWEEN 1 AND 999999999

AND

AnnualSalary BETWEEN 1 AND 999999999;

Here's another approach – how many rows have non-blank values for both OPSTermAmount and AnnualSalary – this should also return 0:

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM florida_positions

WHERE

OPSTermAmount != ''

AND

AnnualSalary != '';

And finally, just to make totally sure that the data is as consistent as it seems to be: let's ask how many rows have blank values for both the OPSTermAmount AND AnnualSalary columns? Again, this should result in 0:

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM florida_positions

WHERE

OPSTermAmount = ''

AND

AnnualSalary = '';

Updating money_amount using two separate UPDATE statements

So basically, I want money_amount to reflect the amount of money a Florida state university employee received, whether it was salary or temp-pay.

The most straightforward way to think of this is 2 different UPDATE statements based on 2 different conditional statements:

1. Setting money_amount to the employee's salary, if applicable

If AnnualSalary is not blank, then set money_amount equal to what's in AnnualSalary. We've essentially done this earlier in the lesson, but no harm in doing it again:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary

WHERE AnnualSalary != '';

2. Setting money_amount to the employee's temp pay, if applicable

Now do the same for non-blank values of OpsTermAmount:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = OPSTermAmount

WHERE OPSTermAmount != '';

Logically, we should be able to run these UPDATE statements over and over and over again. You can even run them both in the SQL client as one query after another:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary

WHERE AnnualSalary != '';

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = OPSTermAmount

WHERE OPSTermAmount != '';

So what's the point of all this? Now we can aggregate and rank schools by the sum of the money_amount column, rather than just either the AnnualSalary or the OpsTermAmount.

Here's a query to show the top 5 Florida universities, ordered by the sum of the money_amount column – I'm also summing the AnnualSalary and OpsTermAmount just for comparison:

SELECT

University,

SUM(AnnualSalary),

SUM(OPSTermAmount),

SUM(money_amount) as total_muns

FROM florida_positions

GROUP BY University

ORDER BY total_muns DESC

LIMIT 5;

| University | SUM(AnnualSalary) | SUM(OPSTermAmount) | total_muns |

|---|---|---|---|

| UF | 1107624366.0 | 59872807.0 | 1167497173 |

| USF | 455211836.0 | 33948786.0 | 489160622 |

| FSU | 390502925.0 | 22904955.0 | 413407880 |

| FIU | 335808488.0 | 11897985.0 | 347706473 |

| UCF | 322528069.0 | 10654698.0 | 333182767 |

As it turns out, OPSTermAmount is a comparatively small part of university budgets compared to the AnnualSalary column. Just how much? Let's do another kind of aggregation that finds the ratio of spending on temp-pay, and rank universities by that number:

SELECT

University,

SUM(OpsTermAmount),

SUM(money_amount) as total_muns,

ROUND(100.0 * SUM(OPSTermAmount) / SUM(money_amount))

AS pct_temp_muns

FROM florida_positions

GROUP BY University

ORDER BY pct_temp_muns DESC

LIMIT 5;

| University | SUM(OpsTermAmount) | total_muns | pct_temp_muns |

|---|---|---|---|

| USF | 33948786.0 | 489160622 | 7.0 |

| FSU | 22904955.0 | 413407880 | 6.0 |

| FAU | 8632644.0 | 186727179 | 5.0 |

| UF | 59872807.0 | 1167497173 | 5.0 |

| FAMU | 3221786.0 | 109130925 | 3.0 |

Dynamic variations of summations

As always, there's more than one way to do things when it comes to programming. Some of you might have noticed that we didn't have to physically add a new column to get the desired money_amount column. We could've created it dynamically, like so:

SELECT

University,

SUM(AnnualSalary),

SUM(OPSTermAmount),

SUM(AnnualSalary + OPSTermAmount) AS total_dynamic_muns

FROM florida_positions

GROUP BY University

ORDER BY total_dynamic_muns DESC

LIMIT 5;

So what was all that work of creating a new column named money_amount? Well, mostly to learn how to add columns and update columns. There are advantages and disadvantages to creating new columns versus dynamically generating them as needed.

The latter approach can be less upfront work. But it can also result in very verbose code. Here's the equivalent, dynamic way of finding percentage of temp-pay spent versus total pay amount:

SELECT

University,

SUM(OpsTermAmount),

SUM(OpsTermAmount + money_amount) AS total_dynamic_muns,

ROUND(100.0 * SUM(OPSTermAmount) / SUM(OpsTermAmount + money_amount))

AS pct_temp_muns

FROM florida_positions

GROUP BY University

ORDER BY pct_temp_muns DESC

LIMIT 5;

What's right? Depends on the situation, really. But take heart that it's not about pure memorization, but understanding the step-by-step logic behind the different approaches.

How to screw things up

Let's close this lesson with examples of how mistakes can be made. Except I won't explain them. These are variations of examples already covered in this lesson – and more importantly, they are all examples of valid SQL. In other words, the SQLite interpreter will not protect you from your own silly, destructive queries.

So skim these examples for fun, and see if you can pick out how the won't result in the data we previously calculated (i.e. the money_amount column).

Examples of not-quite setting money_amount to the intended value

Assuming the money_amount column has been created and you want to set it to the appropriate OPSTermAmount or AnnualSalary value, the following queries all get it wrong, though none of them will throw syntax errors. See if you can figure it out by comparing it to the previous, correct examples:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary;

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = OPSTermAmount;

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary

WHERE AnnualSalary != '';

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary

WHERE OPSTermAmount != '';

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary

WHERE AnnualSalary = '';

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = OPSTermAmount

WHERE OPSTermAmount = '';

Very bad queries

Warning: All of these queries will ruin the original values of OPSTermAmount and/or AnnualSalary. Do not run them unless you have backed up your database. Instead, try to eyeball them and see where things go wrong:

UPDATE florida_positions

SET AnnualSalary = ""

WHERE AnnualSalary != ""

UPDATE florida_positions

SET OPSTermAmount = money_amount

WHERE OPSTermAmount != money_amount;

UPDATE florida_positions

SET AnnualSalary = money_amount

WHERE AnnualSalary != '';

UPDATE florida_positions

SET OPSTermAmount = money_amount

WHERE OPSTermAmount != '';

UPDATE florida_positions

SET money_amount = AnnualSalary

WHERE AnnualSalary != '';

UPDATE florida_positions

SET OPSTermAmount = money_amount

WHERE OPSTermAmount != '';